The EY report showed no demonstrable differences in the quality, accessibility and affordability of care between healthcare institutions partially or wholly owned by private equity firms, and those owned by other organisations. The proportion of healthcare institutions with private equity participation varies per subsector but remains limited overall. VWS is still considering the findings of the research. In our view, the report does not warrant amendments to healthcare laws and regulations. On the contrary, there are several indicators that healthcare institutions with private equity participation show better performance compared to those without such involvement. The findings of the research are particularly relevant in the light of recent parliamentary motions and the current ongoing deliberation of the legislative proposal titled “Integrity business operations of Care and Youth Care Providers” (Wetsvoorstel integere bedrijfsvoering zorg- en jeugdhulpaanbieders) by the Council of State.

Purpose and scope of the research

The research was triggered by increased public and political attention to the role of private equity in healthcare. Following a series of incidents involving commercial chains in the provision of General Practioner (GP) services, and subsequent motions by Members of Parliament, VWS sought an impartial assessment of the impact of private equity in healthcare. Consequently, VWS commissioned EY to investigate two key aspects: (i) the current prevalence of private equity across the different sectors of the healthcare system (funded via the Health Care Insurance Act and the Long-Term Care Act) in terms of numbers and turnover, and (ii) the impact of private equity on the quality, accessibility and affordability of care. The research did not include providers active in other areas of health care, such as youth care and social support (Wmo), nor did it extend to venture capital, which fell outside the research scope.

Definition of private equity

EY defines private equity as a collective term for parties that provide financing solutions, often in the form of a majority stake, to unlisted, established companies. The core activity of a private equity party is to invest in companies, foster their value appreciation and then exit. Throughout this process, private equity is generally not interested in profit distribution, instead using them to further develop the organisation. EY highlights that the focus of private equity lies in the sale value of the organisation on 'exit'.

Scope of private equity financing in healthcare

In total, by using the healthcare-specific merger rulings the Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZa), EY identifies 35 private equity parties active (directly or indirectly) funded via the Zvw/Wlz. Of these, 14 are Dutch private equity parties, while the remaining 21 originate from nine different countries and are active in the Dutch healthcare sector.

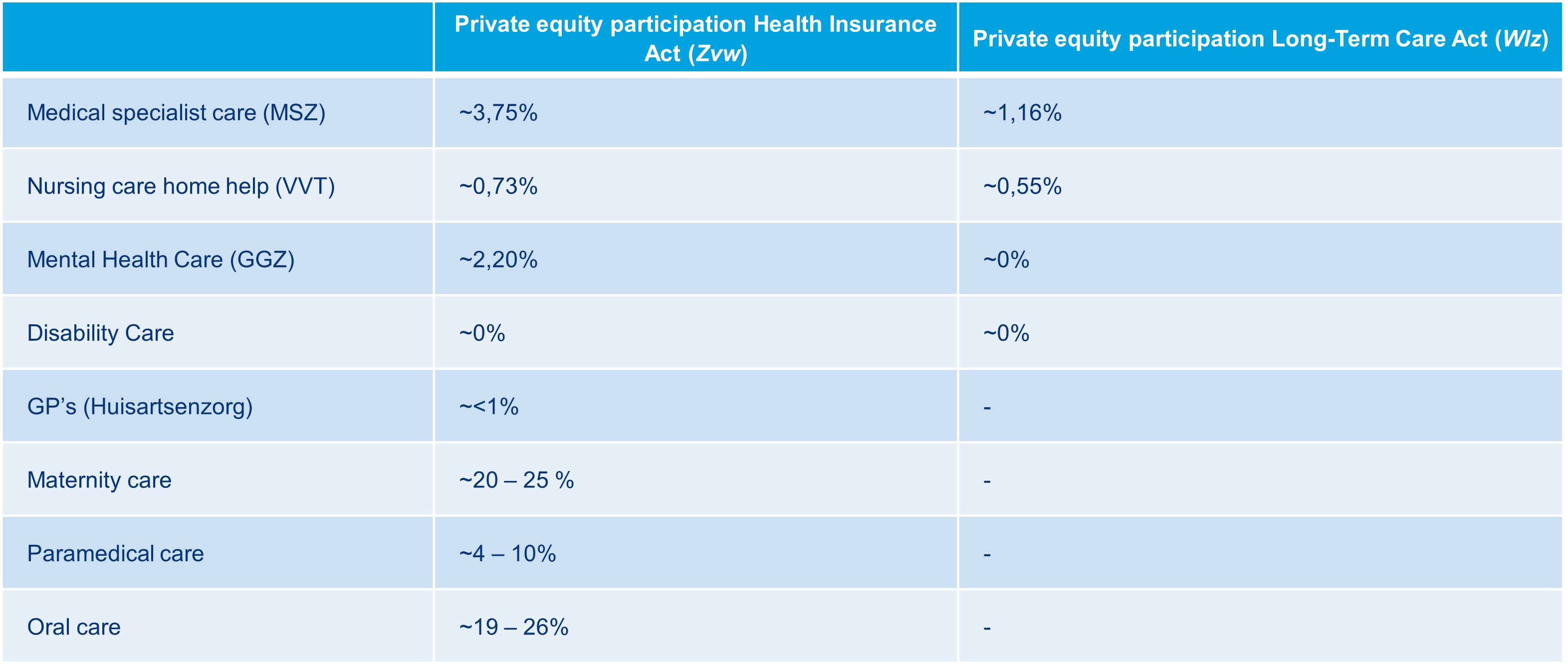

The indicative size of private equity in terms of its share in subsectors funded via the Healthcare Insurance Act (Zvw) and the Long-Term Care Act (Wlz) is shown per sub-sector in the table below:

Private equity participation is highest in oral care, with 11 parties, followed by specialist medical care with 8 parties and the VVT sector with 7 parties.

Amidst the considerable attention garnered by the Co-Med and Centric Health GP chains last year, coupled with the recent (partial) bankruptcy of Co-Med, it is noteworthy that within the GP care subsector, EY identifies only one healthcare institution with private equity participation. This institution’s share of Zvw funds within GP care is estimated at less than ~1%.

Impact of private equity on quality, accessibility and affordability of healthcare

To determine the impact of private equity on the quality, accessibility and affordability of healthcare, EY, in consultation with VWS, selected indicators relevant to measuring the quality, accessibility and affordability of healthcare and drawn from various public data sources and datasets. The in-depth analysis of these factors looked at the primary focus of healthcare institutions and the sub-sectors where private equity operates. The report includes an analysis of the indicators for which sufficient data was available to show the differences between a group of healthcare institutions with private equity participation and a control group of similar healthcare institutions without.

In the research into quality, EY focuses on (i) success and complication rates of operations in specialist medical care (MSZ) clinics, (ii) patient satisfaction with treatment in mental health care (GGZ) and (iii) the results of surveys in maternity care. The research shows no demonstrable differences in the quality indicators examined between healthcare institutions with and without private equity participation. We briefly explain EY's findings for each topic:

- Healthcare institutions with and without private equity participation both score high on indicators (i) percentage of vision gain, (ii) completeness of registrations in the quality register and (iii) accuracy of refractive gain;

- Healthcare institutions with private equity participation score higher on postoperative wound infections and revisions than the group without;

- In healthcare institutions with and without private equity participation, quality of life (measured in PROM scores, Patient-Reported Outcome Measures) improves significantly compared to quality of life before surgery (with minimal difference between the two groups). What is striking is that the outcome of both private equity and non-private equity clinics emerges "particularly favourable" compared to hospitals' reported PROM scores, which are significantly lower.

In the context of patient satisfaction, the group of health care institutions with private equity participation operating within the GGZ has a higher weighted average (8.51/10) compared to the group of health care institutions without private equity participation with a weighted average of (8.15/10).

The largest differences between private and non-private healthcare institutions are in maternity care. EY based its maternity care survey on five indicators. In three of the five indicators, the group of healthcare providers with private equity involvement scored around 5% higher than the group without. However, both types of health care institution scored above 90%.

EY has focused its research on healthcare accessibility on two themes:

- Waiting times within the subsector MSZ by type of care in three disciplines (treatment, diagnostics and outpatient visits); and

- Patient satisfaction with accessibility to a mental health practitioner ("Were you able to contact your practitioner easily").

EY reports the following results in the context of accessibility of care within the subsectors MSZ and GGZ:

- Within orthopaedics and dermatology, the average waiting time for treatment is shorter for the group of healthcare institutions with private equity participation than for the group of healthcare institutions without. Within ophthalmology, the waiting time for treatment is slightly higher for the group of healthcare institutions with private equity participation;

- The average waiting times within the MSZ for an outpatient visit within orthopaedics are longer than for the group of healthcare institutions without private equity participation. Within ophthalmology and dermatology, the waiting time for treatment is slightly higher for the group of healthcare institutions with private equity participation.

- The average waiting time for diagnostics within gynaecology is longer for the group of healthcare institutions with private equity participation than of the group of healthcare institutions without. Within gastrointestinal and liver diseases and radiology, the average waiting time for diagnostics is shorter for the group of healthcare institutions with private equity participation.

- The accessibility within mental health among healthcare institutions without private equity participation is slightly better than the group without. Furthermore, the research shows that the institutions in both groups generally have good accessibility.

EY examined the financial performance of healthcare institutions in the VVT (Verpleging, Verzorging en Thuiszorg) and GGZ (geestelijke gezondheidszorg) sectors, both with and without private equity participation, concentrating on financial indicators such as returns, operating income, liquidity, solvency and operational performance. Operational performance was mapped by absenteeism rates and staff composition.

The findings presented in the report show no demonstrable differences between healthcare institutions with or without private equity participation.

For the research, EY compared the operating income of healthcare institutions with and without private equity participation against the returns of these institutions (returns being calculated by dividing net income by the total operating income). Additionally, EY assessed the financial well-being of healthcare institutions.

The results show that in the VVT sector, there are healthcare institutions in both groups (with and without private equity participation) showing both positive and negative returns. Among those with private equity participation, only one care institution exhibits a negative solvency, while the others display positive values. Similarly, within the group without private equity participation, some healthcare institutions also exhibit negative solvency. However, the majority in both groups demonstrate positive solvency.

Absence rates among the groups within the VVT sector likewise show no noticeable differences, indicating no definitive correlation between private equity participation and increased or decreased absenteeism, or a higher or lower ratio of care professionals to total staff.

The analysis and results concerning financial performance and absenteeism rates within the VVT sector also seem to apply to healthcare institutions within the GGZ sector.

Case studies

The report presents five worthy and readable case studies featuring different private equity parties. These were selected on various indicators, including the subsector in which the healthcare institution operates, the country of origin of the private equity party and their size and investment strategy. Reading these case studies is particularly recommended to get a good idea of how private equity works in the healthcare sector.

Report conclusions

As anticipated, given that quality of care represents value for private equity parties, the research, based on the available data and indicators examined, suggest no notable disparities between healthcare institutions with and without private equity participation in terms of the public interests such as quality, accessibility and affordability. It is important to note that the analyses presented in the report should be considered as indicative and not a basis for definitive conclusions, as stated by EY.

Report consequences

Minister Helder first reaction was a critical response to parliamentary questions and motions regarding private equity in healthcare, each time referencing the EY study. Based partially on this study, the minister will consider whether, and if so which, further measures are necessary to mitigate any negative consequences of private equity. VWS has suggested that the possible extension of the ban on profit distribution for (certain) healthcare institutions could also be an option in this regard. The minister is currently considering the study’s findings and will deliver a substantive response to the report in the second quarter of 2024.

L&L's view

Considering the findings of the EY research, we believe it is prudent to exercise caution in further tightening specific rules for governing private equity in healthcare, especially since there are no demonstrable negative consequences. During the Thirty Members' Debate (Dertigledendebat) on the impact of private equity in healthcare held on 18 April 2024, Minister Helder affirmed that the EY-research in no way provides a legal basis for prohibiting private equity in healthcare. The healthcare sector greatly benefits from investment in healthcare by private equity.

In addition, we note that in 2022, the Wtza entry regime for new healthcare institutions was restricted with the notification and licensing obligation under the Act on Accession of Care Providers (Wtza). The legislative proposal aimed at improving the availability of Youth Care (Wet verbetering beschikbaarheid jeugdzorg) includes obligations regarding the governance structure and financial management of youth care providers. Additionally, the envisaged (new) legal standards outlined in the legislative proposal on Integrity business operations of Care and Youth Care Providers introduce further criteria for sound management and the potential imposition of conditions for profit distribution within specific sub-sectors.

We are monitoring developments closely and will address developments of the Wetsvoorstel integere bedrijfsvoering zorg- en jeugdhulpaanbieders in a subsequent blog. If you have any questions please feel free to get in touch with your usual contact within our Life Sciences & Healthcare Team, or with the undersigned.

NB. Earlier, political excitement about private equity led to studies on the role of private equity in childcare (at the request of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment) and youth care (at the request of the VWS). These showed that private equity contributes to the quality of childcare. Although private equity institutions charge higher prices, there are fewer deficiencies in inspections. Private equity parties are also active in youth care, although they held only 5% of the market in 2022. Research shows that private equity owned youth care providers are less likely to pay dividends and more likely to have a customer board, a supervisory board and an auditor's report.

Click here for the full EY report "Research Private Equity in Healthcare".